Mass Paths

Mass Paths is a series of handcrafted photographs, landscapes of the Irish countryside embedded with absence. They portray the traces of paths walked by Catholics to reach illegal mass during penal times.

The Penal Laws were imposed on Catholics in Ireland in 1695 and religion was prohibited. The Church was kept alive by operating under great secrecy. Dunnett’s aim is to visually unearth the history behind these paths and the people who walked them.

The locations of these sites were passed on by word of mouth. This local knowledge was handed down through generations. The oral tradition in Ireland disappeared gradually during the 1960s alongside land exchange and redevelopment.

Dunnett has spent years researching mass paths and other penal sites, piecing the information together, scouring the internet, finding little snippets posted by schools, regional newspapers and walking clubs. These fragments led to a mapping process, hunting for locations hidden in the landscapes.

She has followed in the footsteps of the thousands of people who walked to penal sites across Ireland. Then recorded these re-enactments in an attempt to capture their stories of resilience, courage and commitment so that they are not lost.

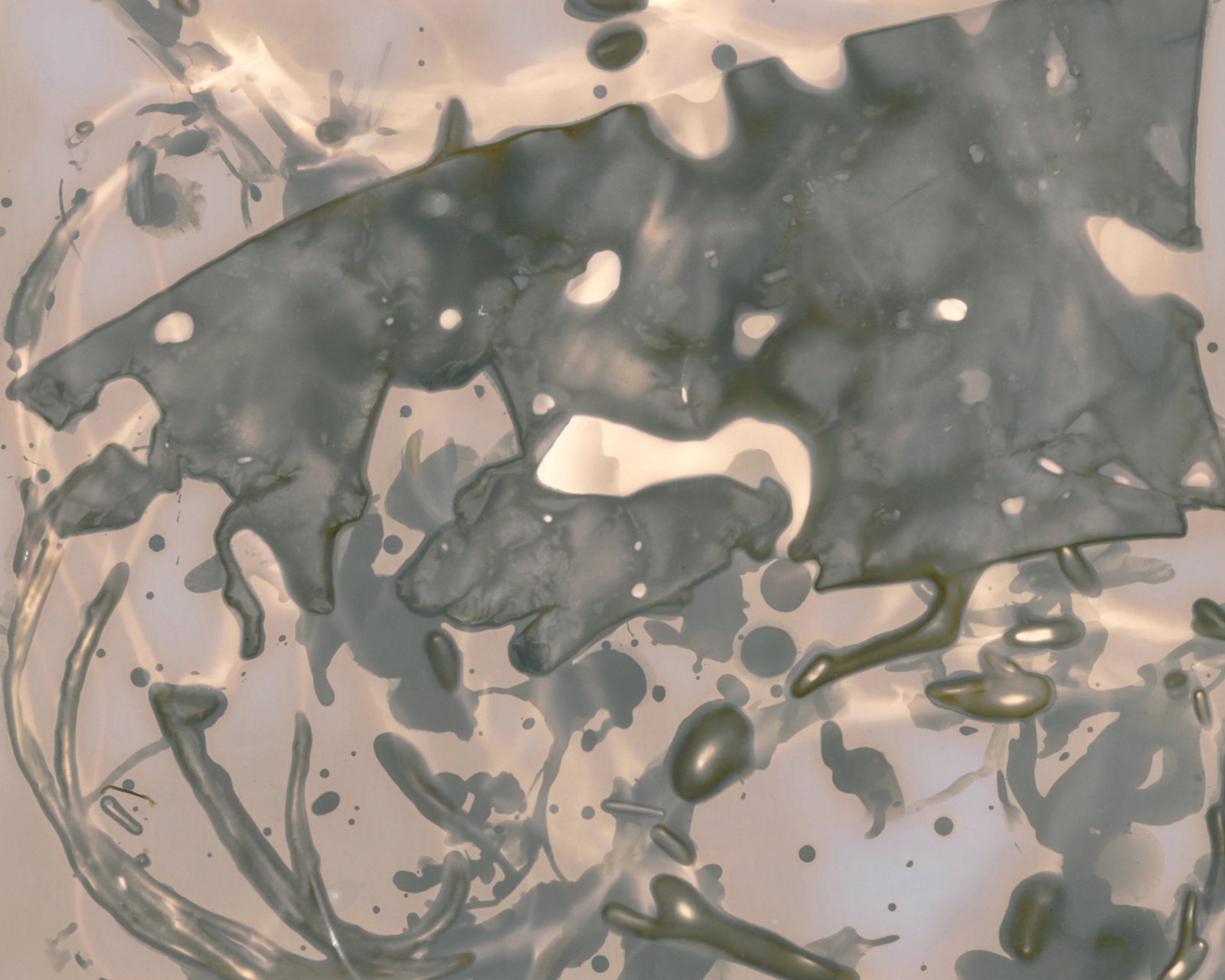

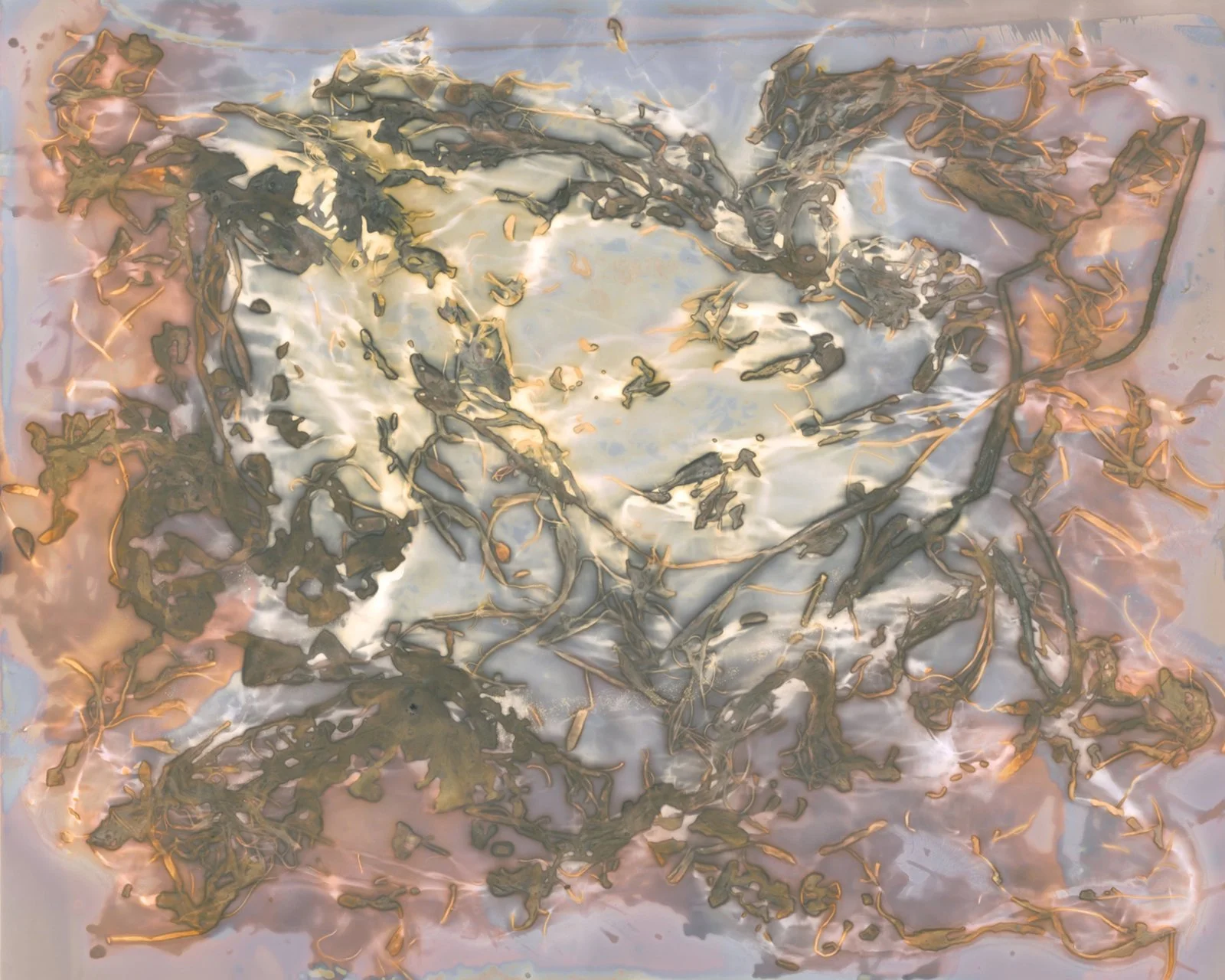

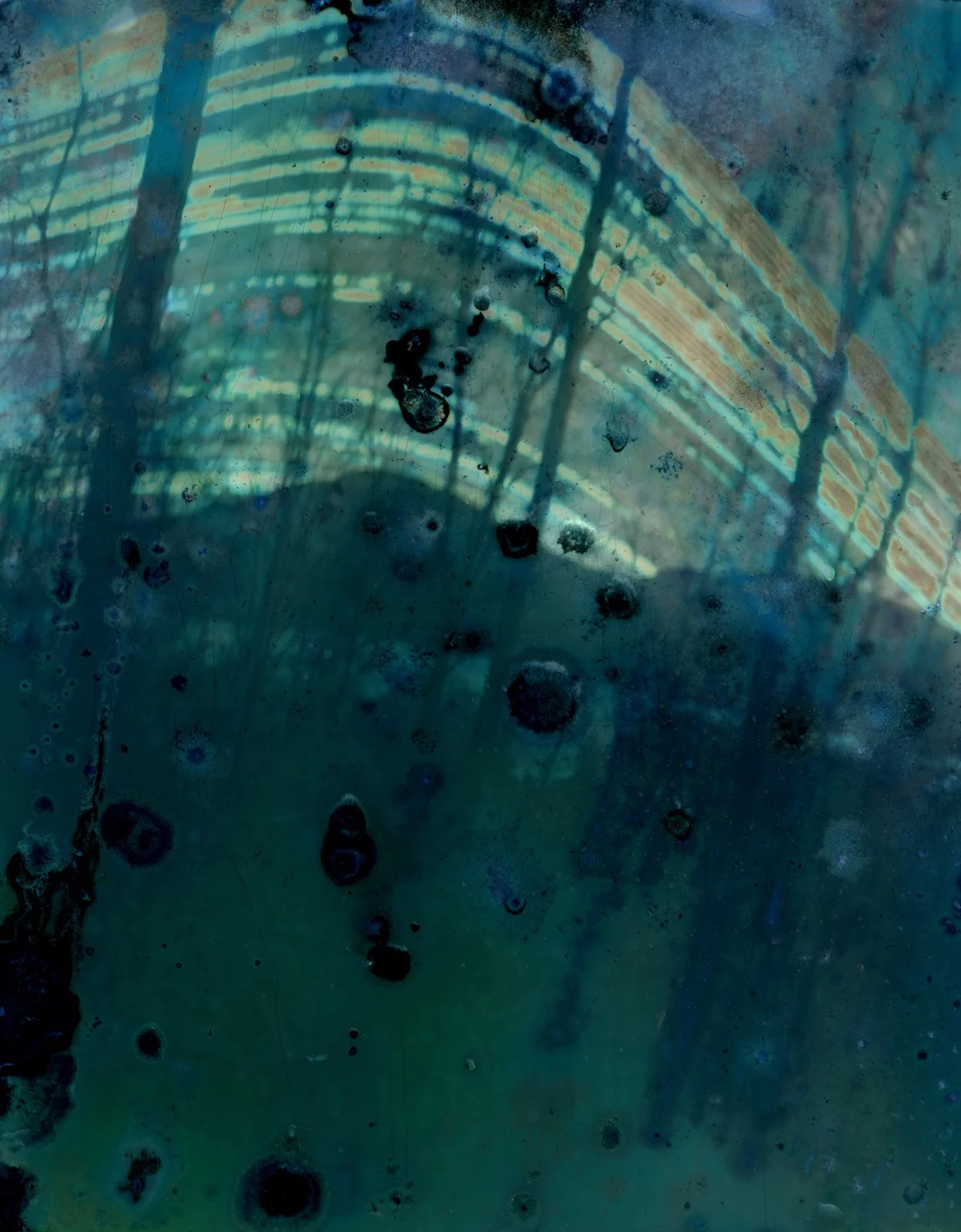

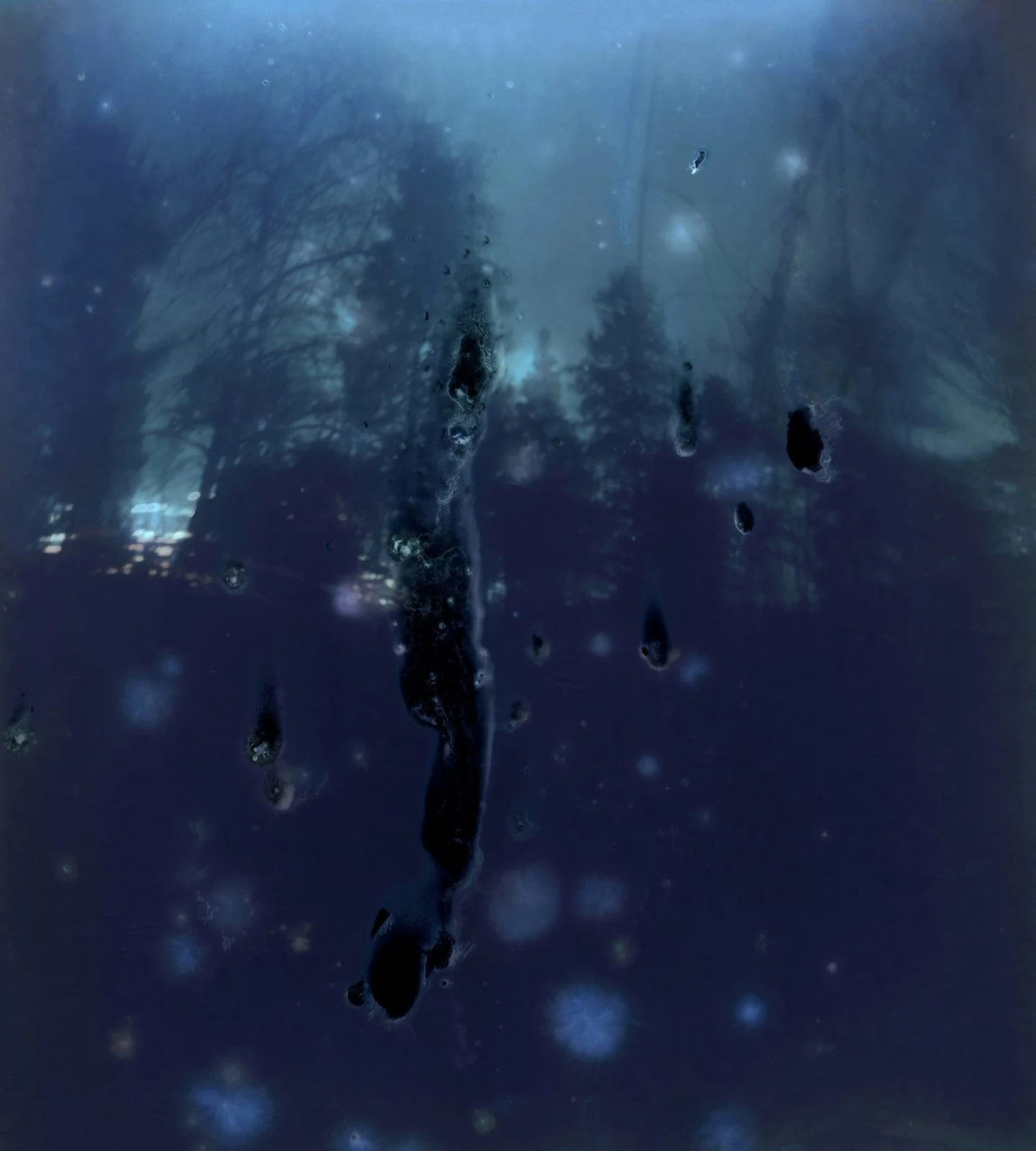

Dunnett has been experimenting with converting the digital photographs of her walks into contact negatives, creating and then toning cyanotypes, opening up a dialogue between photography, painting and etching. She is engaged by how this multi-layered process echoes that of a landscape which has been coated over the years by the complexities and tensions of politics, society, religion and people.

Mass Paths was supported by the Arts Council England.

A Well Trodden Path

Churches in Ireland were built around the country following Catholic Emancipation in 1829 and with them grew networks of mass paths. For decades parishioners from outlying homes journeyed across fields to celebrate mass. A Well Trodden Path explores the heritage of mass paths in the townland of Lackagh in Co Galway. A web of 15 mass paths was mapped out. Fragments of old tracks, stiles and footbridges were pieced together with the recollections of older parishioners.

Mass paths cut across farmland. They were respected and never ploughed. Routes were shaped depending on the condition of the land and largely ran alongside bushes and walls for shelter. The paths were walked in all weathers. A parishioner recalled taking the path with her sister and friends. It took about 2 hours. She wore her old raincoat and shoes. Across her arm she carried her good clothes to change into; after mass she changed back.

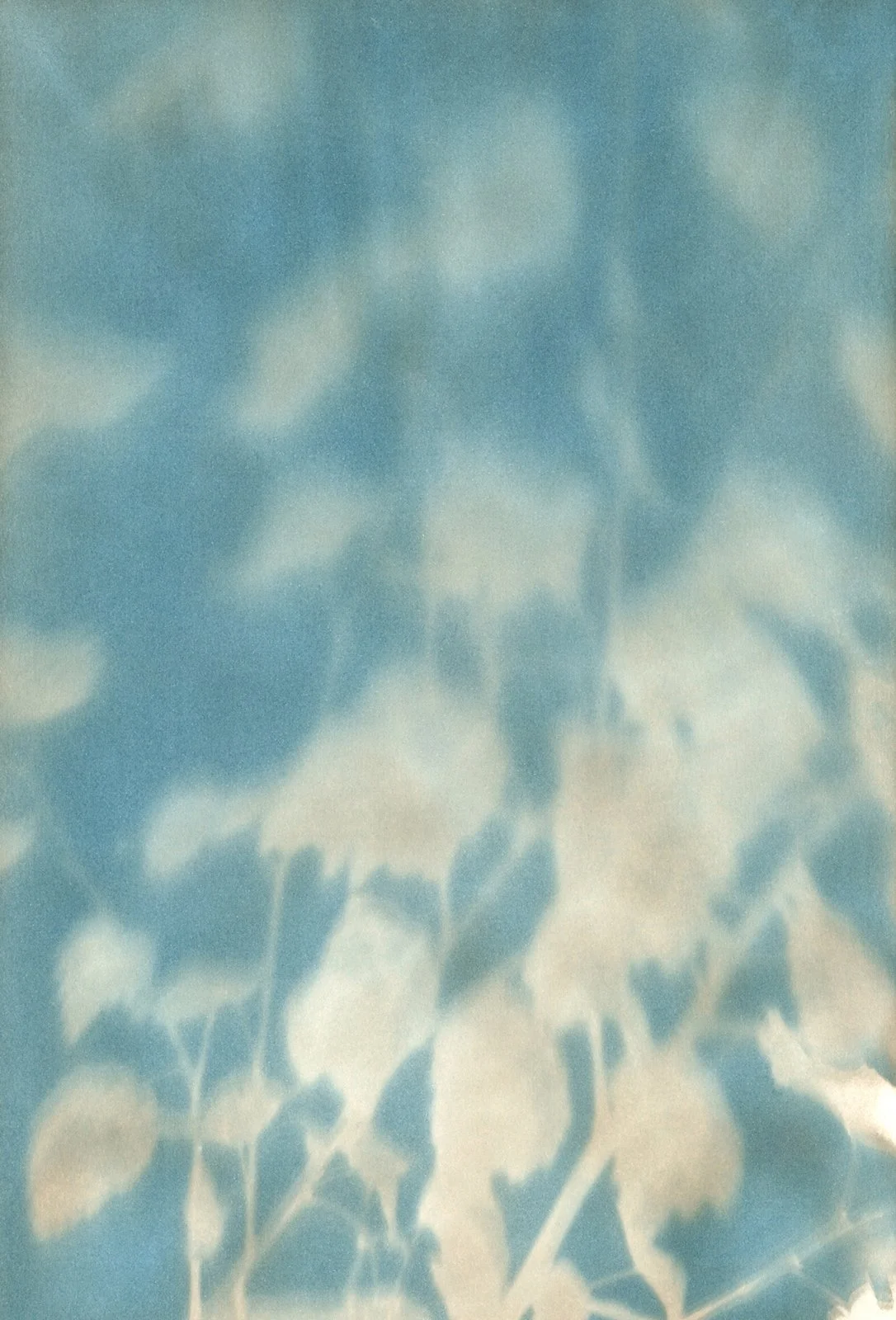

Dunnett photographed traces of these paths. Each had their own traits: beautiful pink and purple grasses, a tunnel of trees illuminating a trail of nettles and big dramatic skies highlighting ancient details. She converted her photographs into contact negatives creating and then toning cyanotypes with a leading brand of Irish tea, a favourite of many who walked the paths. Dunnett layers her work. She is drawn to this process and how it relates to the years of footfall across the fields and the many stories attached.

A Well Trodden Path is a partnership project with Dr. Hilary Bishop, Liverpool John Moores University, funded by the British Academy and supported by NUI Galway, special thanks to Lackagh Museum and Community Development Association and the community of Lackagh.

Family Walks

Family Walks is a series of moments taken from Dunnett’s daily exercise with her family during early lockdown.

In those few months they rediscovered their neighbourhood. They enjoyed meandering, finding pathways that ran across open fields, through small wooded areas and alongside streams. She photographed her family’s exploration of their landscape and delight in the blossoms, dancing shadows and secret passageways.

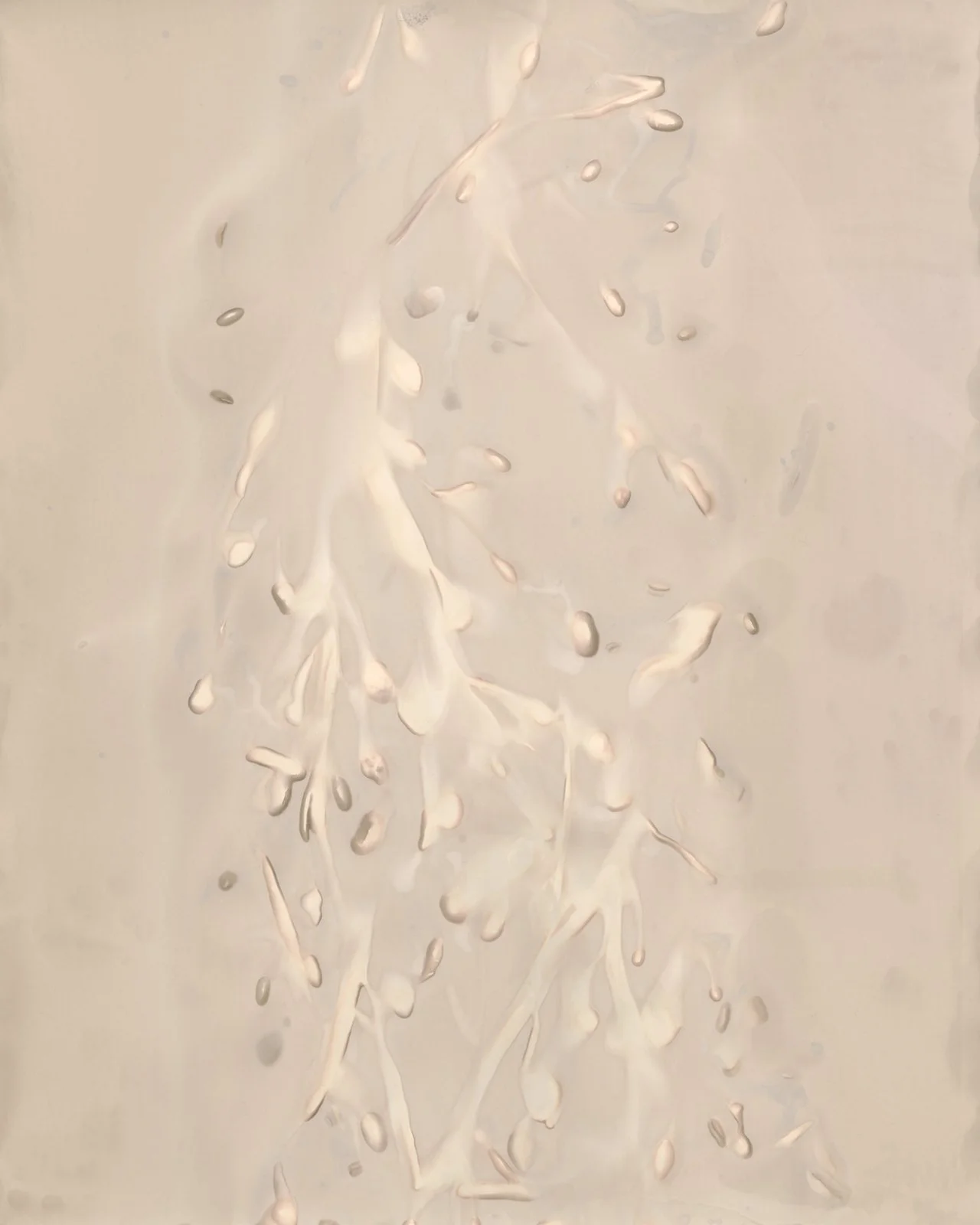

These photographs were used as source images to create Anthotypes, a technique developed by Mary Somerville in 1842 which employs the photosensitivity of plant material to make prints. Dunnett expanded her palette and experimented with emulsions in the kitchen, liquidizing, straining and painting beetroot, blackberries and spinach directly onto paper.

The Anthotypes were exposed in the garden for days and in some cases weeks. They have been digitally recorded. The process is not stable and with time the prints will fade, like her memories of the walks, which were lost when lockdown measures eased.

The Lost Garden

My father grew up in Arrochar, a rural village in Scotland. His father was an armament engineer and worked at the torpedo range. With the job came a house. The family moved in just before the outbreak of WWII. My grandfather lived there for over forty years and cared for his garden. We visited him every summer. I have fond memories of the garden, playing with my brothers and sister.

The garden, house and range were flattened to make way for a development that never materialised. I visited the site a few years back and slipped in behind a fence to photograph the remains. There were daffodils growing amongst the piles of rubble. I took a brick. I wish I had taken a flower.

Working with the fruit, flowers and vegetables that my grandfather tended, I am making lumen prints. Placing plants directly on to photographic paper, the process records the interaction between the plant, surface and light. These traces are fragile and fade with time, like my memories and those of my father who lived with Alzheimer’s. His memories are no more.

The Lost Garden was developed with support from a DYCP Award from Arts Council England.

Hill Close Gardens

Hill Close Gardens captures the timelessness of one of the last groups of detached Victorian pleasure gardens in the UK. The gardens date back to 1845 and were tended by tradesmen. They fell into disrepair and were saved from development by local residents. The plots have been fully restored by volunteers to address the planting of their original owners.

The gardens were invested in, lost and then recreated. Each generation of gardener brought with them a layer of history. Dunnett has created a multi-layered process to engage the gardens past. She converted her photographs into contact negatives to make cyanotypes. Then she toned them with pomegranate referencing 19th century painting and photography.

Dunnett was drawn to the narratives of the tradesmen and photographed their landscaped plots and summerhouses. Whispers and tales from different times follow you around the garden. A sense of peace pays tribute to the years spent cultivating the land. Nature flourishes amongst the hedged plots and Dunnett recalled lost gardens from her childhood. She has explored time’s passage through the gardens and attempted to thread these different layers together.

This series was exhibited at Hill Close Gardens, Warwick during the summer of 2022. It was curated by Alice Swatton and funded by Art Friends of Warwickshire. Grain Projects supported the initial project. Accompanying the exhibition, Dunnett installed lumen prints in progress in 5 of the gardens’ historic summerhouses. She picked a selection of plants from the garden and they were exposed in pre-owned frames of different shapes and sizes.

Dereenacappera

I carried out a place-based enquiry at Dereenacappera on the Beara Peninsula, West Cork. Over two weeks I explored and photographed the land. From Eyeries, I followed the coast to Kilcatherine Point, past the old British Coast Guard Station and the Hag of Beara where the fossilised face of Cailleach Beara can be found staring out to sea, forever waiting for her husband Manannán, the Sea God, to return. Amongst the headstones at the cemetery, were at least fifty rocks. There I met a man who explained that the rocks marked the graves of the Cornish Miners brought over in the 19th century for copper extraction. As the sun dipped, it lit-up the bog’s tall, slender dancing grasses along Lough Fadda.

The landscape disappeared as I looked out across Kenmare Bay. The world turned white. A hailstorm. There was no shelter on the headland, just a grassy ridge. It lifted and a rainbow framed Dogs Point. I walked over and back a few times to Ardgroom along the Beara Way, in all weathers passing the shell of an old cottage. I looked out for it each time and photographed it. I continued onto Glenbeg Lough, hidden in the mountains. The water glistened as I followed the shoreline. On my last day I walked from Lauragh to Ardgroom and back to Dereenacappera. I followed the old Kenmare Road. Jagged rocks covered the mountain, like the back of a sleeping ankylosaurus. The light changed and became heavy; the rest of the walk was hard. Up and down, down and up the mountain following the farmers’ fields.

There I developed new ways of working and incorporating the land into my process. I learnt about seaweeds and plants from artist Frieda Meany’s local knowledge. Working with cameraless processes, I produced cyanotypes and phytograms with seaweed, bog and forest plants. As well as chemigrams with alternative developers made out of seaweed, nettles and 4000-year-old bog pine. The photographs taken on my walks were used to create cyanotypes and anthotypes. I experimented with emulsions, these included blackberry, fuchsia, gorse petals, a nettle and ivy combination, ragwort and sea beet. I collected oak galls and toned my cyanotypes.

Dereenacappera was supported by the Arts Council Ireland.

The Low Road work-in-progress

My father grew up in Arrochar, a rural village at the head of Loch Long, Scotland. I spent many childhood summers there. I hadn’t been back in years, until he passed away. Through grief I have reconnected with the loch and its landscape.

I have recorded familial recollections, stories and my engagement with the land. My great-grandparents were employed at Ardmay House, a Victorian fishing lodge on the shore of Loch Long. He was a gardener and she worked in the house with two of their daughters, my grandmother, Marica, and her sister, Helen. Later they took up positions at Ardgartan House, on the opposite side of the loch. The house is long gone, there now stands a grand hotel, a fixture in the landscape.

My grandfather was an armament engineer and worked at the torpedo range on the loch. The range was a hub of activity during the war years. Over sixty torpedoes were fired per day. Local men and women were deployed as part of the war effort to retrieve them. It’s quiet now, with just the remains of a few long-lost torpedoes resting peacefully on the loch’s bed and the home of the UK nuclear weapons programme downstream.

I have been integrating the land into my process through alternative photography processes. My methods are slow, creating connections with time. I produced cyanotypes from photographs and toned them with plants foraged from the loch’s environs, such as acorns and ragwort. I placed pinhole cameras in the landscape and explored time through solargraphy. I have been catching the sun’s travels, recording the elements and the corrosion of the camera on photographic paper. Working with camera-less processes on the shore and banks of the loch, I have documented interactions between plants and the environment.

We visited my grandfather every summer and swam in the same place, to the left below the range and away from the fences. I can remember my father’s routine to ease himself into the cold water. The water is still cold.

The Low Road has been supported by the Richard and Siobhán Coward Foundation, a-n the Artist Information Company, the Hope Scott Trust, CuratorSpace and the Eaton Fund.